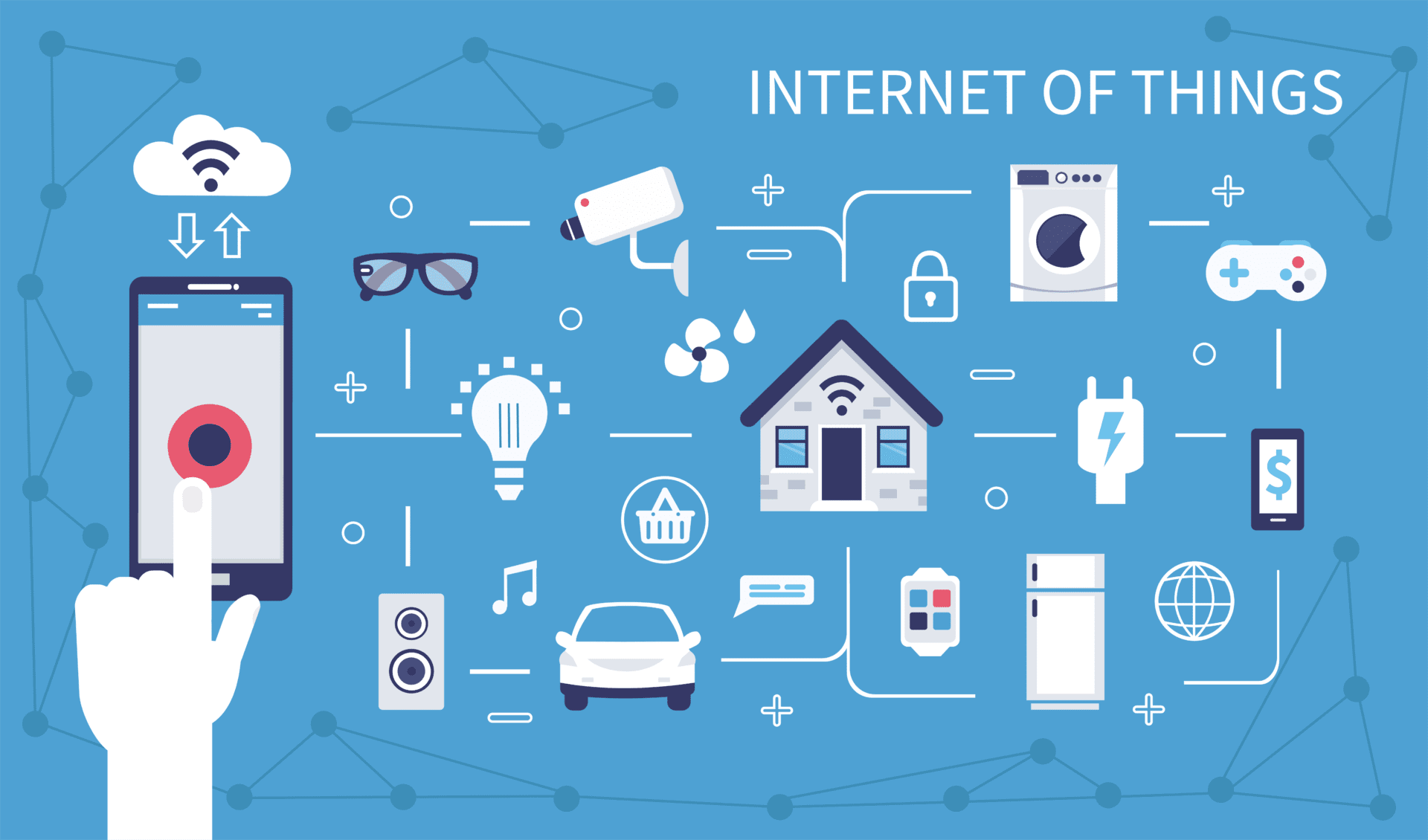

The Internet of Things (IoT) has rapidly transformed the way we live and work. By connecting everyday objects to the internet, IoT has created a network of devices that communicate and share data, leading to unprecedented advancements in various industries. In this article, we will explore different IoT solutions and services, their key features, benefits, challenges, and future trends.

Overview of IoT Solutions and Services

IoT solutions encompass a wide range of services and products designed to enhance connectivity and data exchange between devices. These solutions can be broadly categorized into consumer IoT, industrial IoT (IIoT), smart home solutions, and wearable devices. Each category offers unique applications and benefits, making IoT a versatile and essential technology in today’s digital age.

Types of IoT Solutions

Consumer IoT

Consumer IoT solutions are designed for everyday use, enhancing the convenience and efficiency of daily activities. This category includes smart home devices like smart thermostats, security cameras, and voice assistants. These devices help automate home environments, providing users with greater control and energy efficiency. For instance, smart thermostats can learn user preferences and adjust heating and cooling systems accordingly, leading to significant energy savings.

Industrial IoT (IIoT)

Industrial IoT focuses on optimizing industrial processes and operations. IIoT solutions include advanced sensors, predictive maintenance systems, and automated machinery. These technologies are used in manufacturing, agriculture, and logistics to improve productivity, reduce downtime, and enhance safety. In agriculture, for example, IoT sensors can monitor soil conditions and crop health, allowing farmers to optimize irrigation and fertilization processes.

Smart Home Solutions

Smart home solutions integrate various IoT devices to create a cohesive, automated home environment. This includes smart lighting systems, connected appliances, and home security systems. Smart home solutions offer convenience, energy savings, and enhanced security, making homes more intelligent and responsive. With smart lighting systems, users can control lights remotely or set schedules, ensuring lights are only on when needed, thus saving energy.

Wearable Devices

Wearable IoT devices, such as fitness trackers and smartwatches, monitor and collect health-related data. These devices provide real-time feedback on physical activity, heart rate, and sleep patterns. Wearable technology helps users track their fitness goals, monitor health conditions, and stay connected on the go. For instance, fitness trackers can remind users to move if they have been inactive for too long, promoting a healthier lifestyle.

Key Features of IoT Solutions

IoT solutions come with several key features that make them indispensable in various applications. The primary feature is connectivity, which allows devices to connect and exchange data seamlessly. Real-time monitoring is another essential feature, enabling continuous data collection and providing immediate insights. Automation is a significant advantage, allowing devices to operate based on pre-set conditions, reducing the need for human intervention. Additionally, data analytics processes and analyzes large volumes of data, offering valuable insights for decision-making. Scalability ensures that IoT systems can expand and accommodate more devices and data over time, making them future-proof and adaptable.

Benefits of Implementing IoT Solutions

Implementing IoT solutions offers numerous benefits for both consumers and businesses. Enhanced efficiency is one of the most notable advantages, as IoT solutions automate tasks and processes, leading to increased productivity. For example, in manufacturing, automated machinery can operate with minimal human intervention, reducing errors and speeding up production. IoT solutions also help save costs by optimizing resource use and reducing waste. Smart energy management systems, for instance, can significantly reduce electricity bills by optimizing power usage.

Improved decision-making is another significant benefit, as real-time data and analytics provide valuable insights that enable better strategic decisions. Businesses can use data from IoT devices to identify trends and optimize operations. Additionally, IoT devices simplify everyday tasks, offering greater convenience and control. Voice assistants like Amazon Alexa or Google Assistant allow users to control various smart home devices through simple voice commands. IoT solutions also improve safety and security in homes and workplaces through advanced monitoring and alerts. For instance, smart security cameras can detect unusual activity and send instant alerts to homeowners, enhancing security.

Challenges in IoT Implementation

Despite its numerous benefits, IoT implementation faces several challenges. Security concerns are paramount, as the increased number of connected devices raises the risk of cyber-attacks and data breaches. Ensuring robust security measures for IoT devices is crucial to protect sensitive data. Interoperability issues also pose a challenge, as ensuring different IoT devices and platforms work seamlessly together can be difficult. Standardizing communication protocols can help address this issue.

Data privacy is another critical concern, as the collection and use of personal data by IoT devices raise privacy issues. Clear policies and regulations are needed to ensure user data is protected and used ethically. High initial costs can also be a barrier, as implementing IoT solutions often requires significant upfront investment. However, the long-term benefits usually outweigh the initial costs. Lastly, the complexity of setting up and managing IoT systems can be daunting and require specialized knowledge. Investing in training and hiring skilled professionals can help mitigate this challenge.

Future Trends in IoT

The future of IoT is promising, with several trends expected to shape its development. One of the most significant trends is the integration of 5G networks, which will enhance IoT connectivity, enabling faster data transmission and more reliable connections. This will allow for more sophisticated IoT applications and real-time processing of large data sets. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) will also play a crucial role in driving advanced analytics and automation in IoT, making devices smarter and more responsive. Predictive maintenance systems powered by AI can forecast equipment failures and schedule timely repairs.

Edge computing is another emerging trend, where data is processed closer to where it is generated (at the edge), reducing latency and improving real-time analytics. This is particularly important for applications that require immediate responses, such as autonomous vehicles. Enhanced security solutions will continue to be developed as security remains a concern. Blockchain technology is being explored as a means to secure IoT data and transactions. Sustainability will also be a focus, with IoT solutions helping reduce energy consumption and promote green practices. Smart grids and energy management systems can optimize power distribution and reduce carbon footprints.

Conclusion

IoT solutions and services are revolutionizing various aspects of our lives, from enhancing home automation to optimizing industrial processes. While there are challenges to overcome, the benefits and future potential of IoT are immense. As technology continues to advance, IoT will play an increasingly critical role in driving innovation and improving efficiency across different sectors. Now is the time for businesses and consumers alike to explore and adopt IoT solutions to stay ahead in this connected world.